Tools For Digital Sovereignty: Operating Systems [2023]

Building on Part 2, this piece looks at “operating systems”, and how we can use operating systems that keep out the Big Tech companies that do not respect our freedoms. Part 3 of 6.

In the previous piece, we began to explore different software that can promote digital sovereignty, based on some of the principles and ideas we introduced in Part 1. Today, I want to go one step further and look at “operating systems”, and how we can use operating systems that keep out the Big Tech companies that do not respect our freedoms.

As a preface, this is not going to be a tutorial for installing and setting up different operating systems. This is partly because there can be slight differences and discrepancies in the methods used depending on devices, computer specifications and so forth. As such, I would much rather introduce a lot of the general concepts and ideas, link to some useful external resources where relevant, and trust that those reading this article can begin to pull all those together in working out what the best approaches are for them. I may release a piece at the end of the Digital Sovereignty Series showing exactly how I would set up a sovereignty-respecting computer and technology setup for myself to illustrate some of these ideas more tangibly, if there is demand for me to do so.

What Is An "Operating System"?

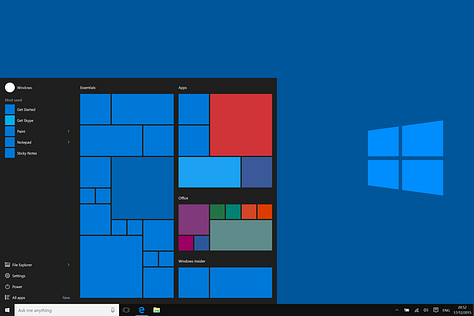

Most of us are probably familiar with the idea of “Windows” computers and “Apple” or “Mac” computers. This is perhaps the easiest example to give where the key difference between these systems is the operating system. At a fundamental level, these operating systems are pieces of software that act as a bridge between the physical components that make up our computers and the applications and programs we download and use. It helps work out how much processing power should be directed at different applications at different times to allow multi-tasking. It can also provide additional applications to help in the running and maintenance of the computer, such as built-in antivirus software, file managers and so forth.

For computers and laptops, the most dominant operating systems are Windows, developed by Microsoft, MacOS, developed by Apple, and Chrome OS, developed by Google. Just by the names alone, it is clear to see the stranglehold that the Big Tech firms have on operating systems. But why is that an issue?

For starters, Windows is notorious for having tons of trackers that send data to Microsoft about what you are using your computer to do. Not only can this constitute as a violation of privacy, but also slows down computers by directing away processing power that would be used on running the programs we want to be using. MacOS, while not as well-known for is trackers, is designed specifically to run on Apple-produced computers, which sell for a premium price point. Their operating system is also closed-source, meaning we don’t fully know how the system is processing data. Let us not forget that Apple, like Microsoft and Google, is also an important partner of the World Economic Forum, which should give anyone cause for concern. Google’s offerings are based on their web browser, Chrome, which has been noted for concerning privacy practises. This is before even considering the practical downfalls of Chrome OS, with its need to have a constant internet connection to be used properly and its incompatibilities with lots of other software.

Introducing Linux

Thankfully, there is a family of operating systems that can address many of the faults the other Big Tech operating systems suffer from. “Linux” began life as a hobby project by Linus Torvalds while studying at Helsinki University in the early 1990s. Torvalds looked to provide an experience similar to the operating systems he used in university, only for free. After Torvalds shared some early prototypes online, interest quickly grew in the idea of an open-source operating system. A team of developers soon formed around Torvalds culminating in the first official version of the software in 1994.

Thanks to Torvald’s commitment to open-source, there are now many different implementations of Linux for a variety of needs, typically referred to as different “distributions”. These are not just limited to home computers, but servers and even Android phones, such as the Google Pixel, have been made using a Linux “kernel” – or the core part of the Linux operating system. There is a huge decentralised tech culture and “do-it-yourself” mentality associated with Linux, whereby anyone anywhere in the world can build their own operating system based on the code and programs written by Torvalds and his team, whether for personal use or for others to enjoy.

Perhaps the only downside to this mentality is that it expects users to take initiative on how they want to use the system – as well as any problems they may encounter while using it. This perhaps makes it slightly more difficult to use than a heavily centralised system with official support networks, but I would say it’s absolutely worthwhile taking on the responsibility. One of the big positives of the past few years is that it has encouraged ordinary people to take control of their own health, understanding their bodies and what they need to live healthily, happily and freely, even though this is more effort than relying on a central health service or unaccountable NGO to tell us what we should be doing with our bodies. In my mind, technology should be no different, and Linux systems are just one example of how that can be achieved.

With all that said, many popular distributions nowadays have a great deal of focus on being friendly to new users, including those coming over from Windows and Apple systems. With this, there are generally community forums and encyclopaedias which have proved particularly useful for me if I have ever encountered problems. In the remainder of this piece, I’d like to highlight a few distributions that have particularly impressed me and, in doing so, explore some of the other interesting features that many Linux systems include which set themselves apart from the other systems we may be used to.

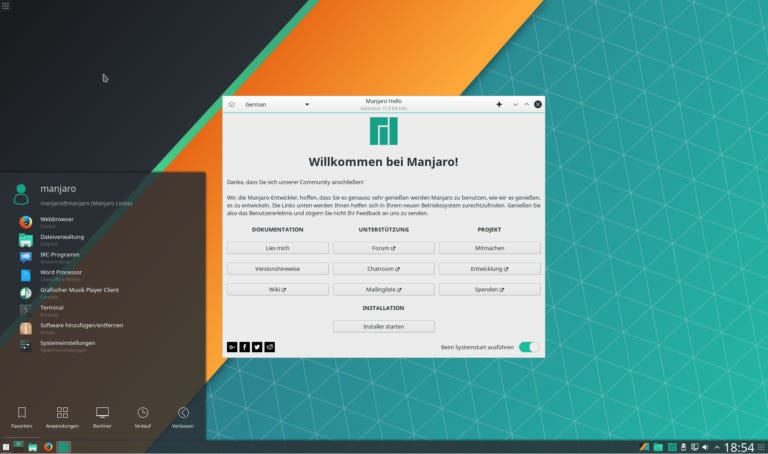

Manjaro Linux

Manjaro Linux, or simply Manjaro, is one of the most popular Linux systems used today, and is the system I personally have most experience with. I think its popularity can be attributed to combining an experience that is friendly to new users, while also giving freedom to customise almost all aspects of the system to a users liking. Manjaro was first released in 2011 as a hobby project on an online forum, and since then the company Manjaro GmbH & Co. KG has since formed to facilitate its development. That said, Manjaro makes a point to be heavily involved with the community it uses, allowing its community to directly contribute to the coding and documentation of the system amongst other things.

As a result, Manjaro has, in my view, some of the best documentation available for a Linux system, not to mention countless independent videos and guides online covering the system. Moreover, as Manjaro is based on Arch Linux – another Linux distribution – many of the guides and resources of the Arch Linux Wiki work perfectly on Manjaro, providing another means of being able to solve any problems someone might encounter. It is also designed to work with many different makes and models of computer, with a few minimum requirements on things like memory size and processing power.

How Manjaro Compares To Other Operating Systems

I’ve found a number of practical advantages to using Manjaro, and Linux systems in general, compared to Windows too (which is what I used previously). Firstly, I have had far fewer crashes than when I used Windows. I suspect this is partly due to Linux developers generally being motivated to create good, efficient software because its something they would want to use themselves, rather than for money. It could also be a by-product of Linux systems generally needing less processing power and memory than something like Windows. I also have a lot more control over the system than I do when using Windows; there are no restrictions on me uninstalling pre-included programs that I don’t use, or in changing settings so that programs run the way I want them to.

Manjaro does show some important differences for both installation and day-to-day use compared to Windows, though. Navigating to the downloads page of Manjaro, a choice between 9 different “images” is available. Each of these “images” refer to different pre-bundled desktops that determine how Manjaro looks visually. The “Plasma” image offers a very modern Windows-like experience, and I would generally recommend this for anyone starting out with Manjaro. “Xfce” is a great choice for those looking to run Manjaro on older computers as it doesn’t use as many system resources when running, and feels a lot like older versions of Windows like Windows XP or Windows 7. The “GNOME” desktop offers something that feels very similar to Apple systems, although has required a bit more setup to get it working the way I would like than some of the other desktops.

The next key difference to note is in how Linux systems are installed. The downloaded “ISO” file must be “burned” to either a CD or USB, similar to how I would “burn” music to a CD to play in a CD player. Loading into a “burned” USB/CD containing Manjaro, or certain other Linux distributions, will load what’s called a “Live Environment”. This lets someone initially test what the operating system looks and feels like without having to install it on their computer first. If, for whatever reason, someone tried out this “Live Environment” and didn’t want to install Manjaro, they could just turn off the system, remove the USB/CD and reboot back into whatever operating system they used before, with all their old files and programs untouched. For those who do want to install Manjaro permanently, this can be done inside the “Live Environment” using an easy-to-follow installer.

When using Linux systems, there are a few useful things to know about how they work that differ from something like Windows or Apple systems. Firstly, there are differences in where Linux stores different files compared to Windows/Apple, including where downloaded programs are stored, where the operating system files are kept, and where personal files and documents are kept, for example.

Next, it should be noted that new programs are generally downloaded using a “Package Manager”, rather than going to a website to download whatever application is desired. A Package Manager can be thought of as a kind of App Store, which keeps a track of links to all the software that can be run on the system and lets users know when updates are available. There are other ways of installing programs, but this tends to be the best way for both new and experienced users to get the latest versions of the software they need.

It is highly possible that there will be programs someone may have used on a Windows or Apple machine which, by default, are not normally available. When something like this happens for me, I’ll see if I can answer the following questions:

Is there a free, open-source alternative to the program I was using before that is already available from the Package Manager? Some of the programs I mentioned in Part 2 of this series, such as LibreOffice and Brave Browser, are great examples of that.

Are there any other sources of software my Package Manager can look for that contain the program I need? A great example of this in Manjaro Linux is the “Arch User Repository” which, once enabled and set up correctly, has allowed me to install and run programs like Spotify and Zoom.

Can I just use the Windows version of the software on Linux? Sometimes, yes! There’s a very well-known Linux program called WINE which, to simplify, can translate Windows installer files into Linux ones. I haven’t found the need to use this as yet, and it doesn’t always work perfectly, but it can sometimes be a life-saver if there’s a program someone absolutely needs that is only available on Windows.

One final thing to note is that, while Manjaro allows a user to manage most of the system through visual applications, like someone would on Windows or Apple, there are times when knowing “command line” or “terminal” inputs can be very useful. This involves manually typing out a command to tell the computer to do a specific action. While this might be familiar for those reading who remember the early days of home computers, I admit this can look quite scary to anyone who isn’t comfortable with typing in commands. I generally just tend to look these up as and when I might need them. I’ll link some resources here and here which can act as gradual entry-ways into the world of command lines.

Other Linux Systems

Manjaro Linux is by no means the only distribution of Linux available, numbering well into the hundreds. Here are some other ones worth mentioning:

Ubuntu and Mint: Like Manjaro, these systems focus on providing a standard home computer experience that is accessible to new users.

Tails & KodachiOS: These two Linux operating systems are purpose-built to run off of USBs using the “Live Environment” feature we discussed earlier, without being permanently installed on the computer. This is done partly for added security reasons; Tails can route all internet communications through the Tor network (which we introduced in Part 2), and KodachiOS goes further, incorporating a Virtual Private Network and extra encryption alongside the Tor network. These are probably more useful for those looking to avoid being detected online, like whistleblowers or activists at significant risk of being persecuted, and who may need to use whatever computer they can get their hands on to carry out the work they need to.

antiX: This distribution of Linux is specifically designed with the intention of being able to run on older devices. I have some experience in using antiX as means of “reviving” old laptops who have become so slow from Windows updates that they are essentially unusable. The same community behind antiX also contribute to MX Linux, which tries to be a mid-point between a highly polished user experience like Manjaro and a super-lightweight distribution like antiX.

The website DistroWatch does a great job at keeping track of different Linux distributions and their popularity.

Final Thoughts

I hope this article has successfully introduced some ideas on how operating systems, like those in the Linux family, can be used in a way that promotes digital sovereignty. Linux systems do demand more of their users than Windows or Apple systems do, however the rewards for doing so, in my view, far outweigh the extra effort needed to take on that responsibility.

For those interested in learning more about the origins of Linux, Linus Torvalds has a well-received autobiography entitled “Just For Fun: The Story Of An Accidental Revolutionary”, exploring his history with developing Linux and how it came to be the tool it is today.

For learning more about using Linux, this article is a good place for those who might be brand-new to the system. The Free Software Foundation, who was linked at the end of Part 1, maintain a directory of “free” software, which meets their standards as it pertains to promoting digital sovereignty and much of which is available to use on Linux systems.